# Training the network

history = model.fit(

X_train[:10000,:], train_labels[:10000],

epochs=50, batch_size=64, verbose=0,

validation_split=0.1)

# evaluation

loss, accuracy = model.evaluate(

X_test, test_labels, verbose=0)

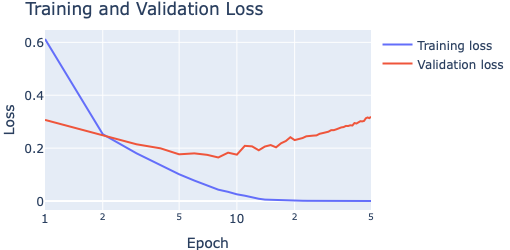

# Extract loss values

train_loss = history.history['loss']

val_loss = history.history['val_loss']

# Plot the learning curves

epochs = list(range(1, len(train_loss) + 1))

fig1 = go.Figure(go.Scatter(

x=epochs, y=train_loss, name="Training loss"))

fig1.add_trace(

go.Scatter(x=epochs, y=val_loss,

name="Training loss"))

fig1.update_layout(

title="Training and Validation Loss",

width=510, height=250,

xaxis=dict(title="Epoch", type="log"),

yaxis=dict(title="Loss"))

fig1.show()

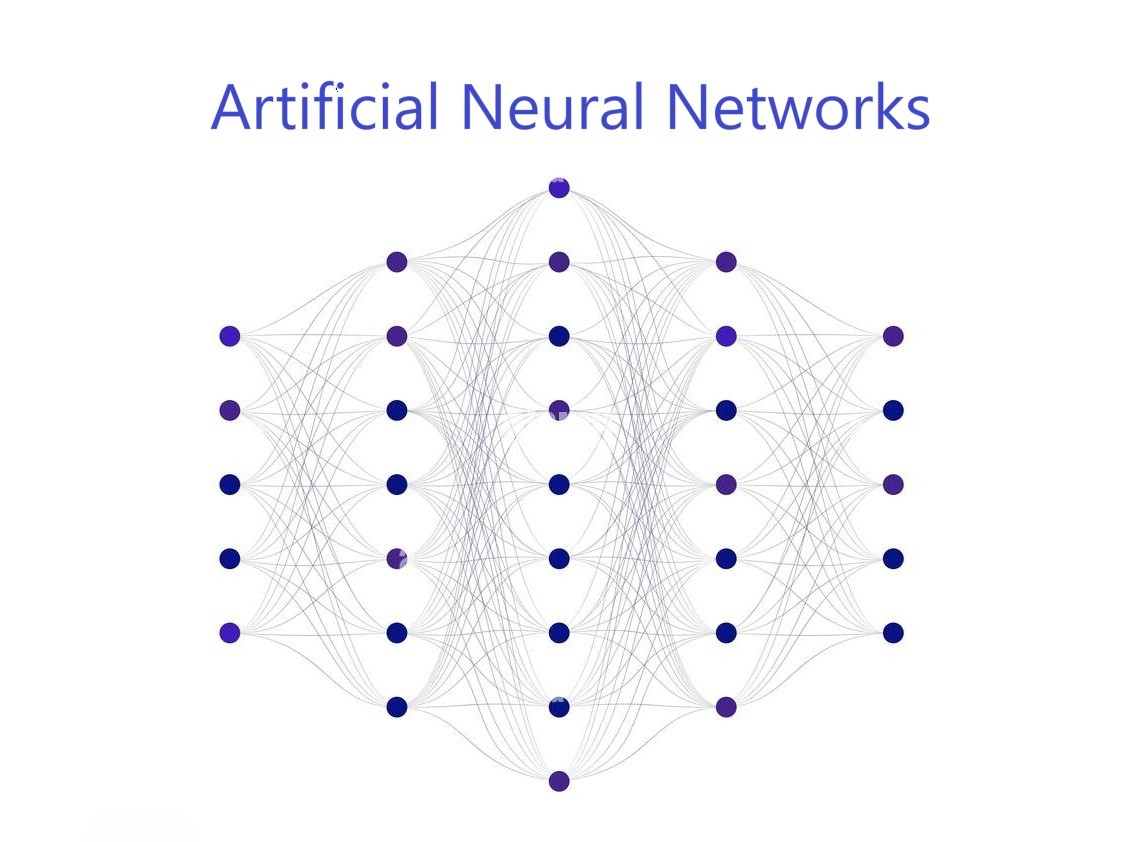

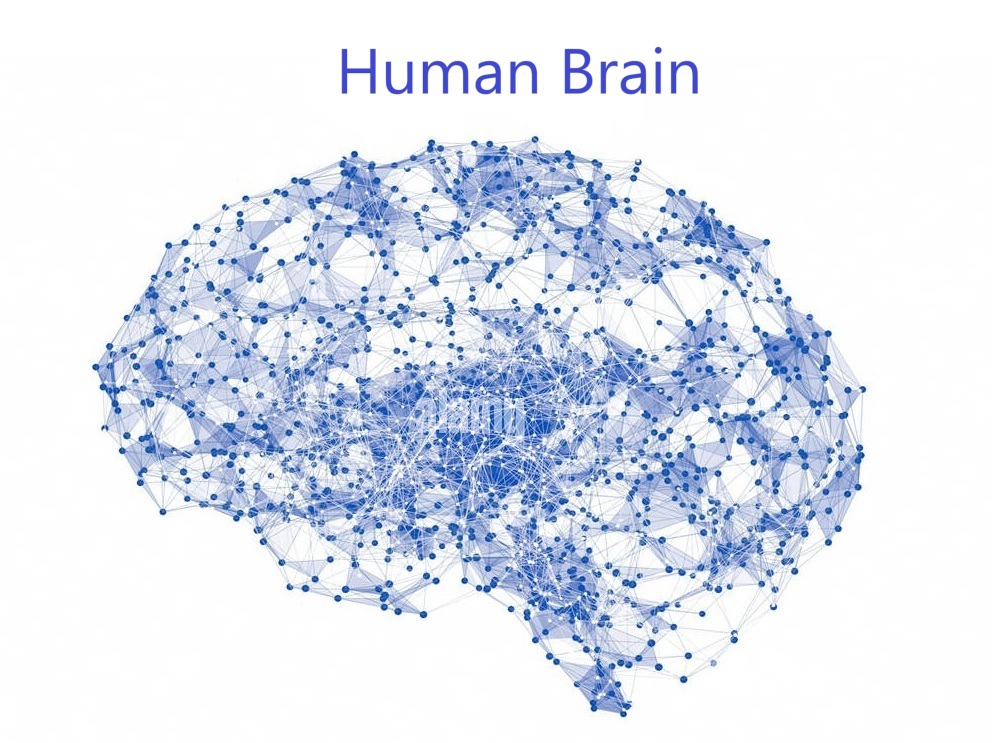

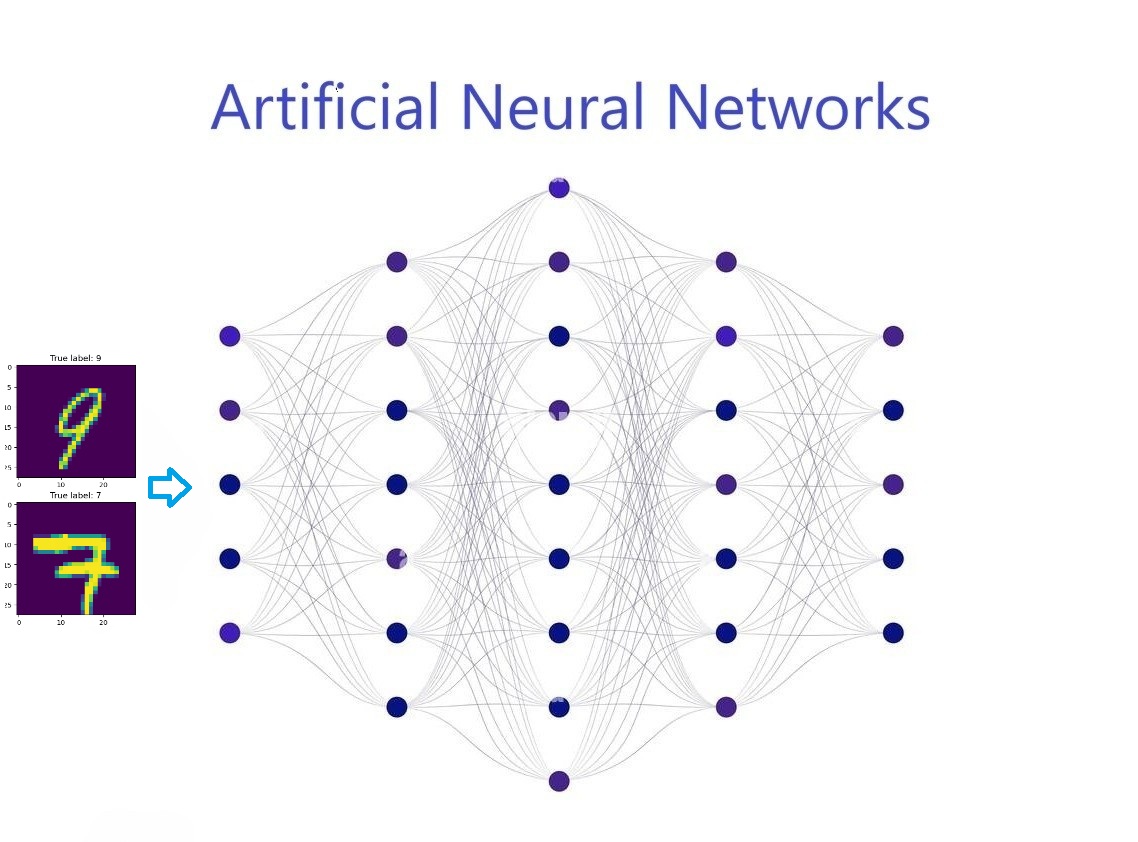

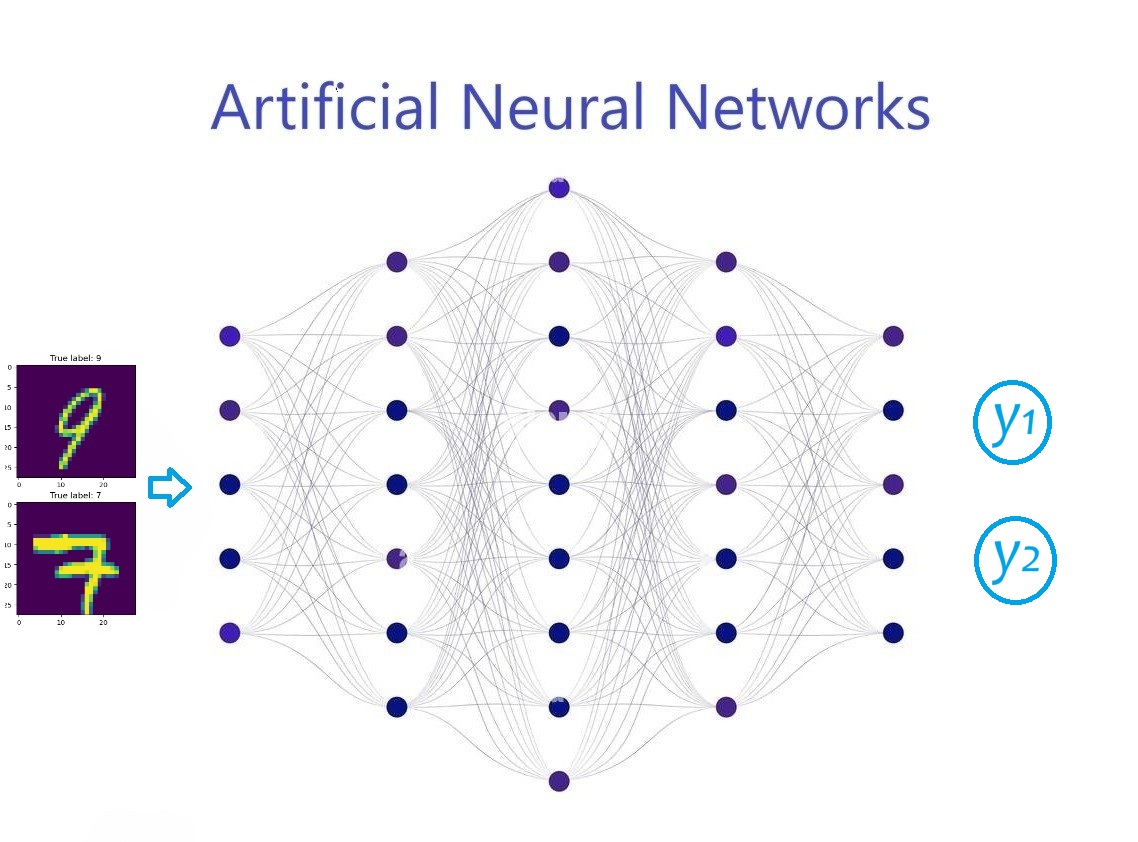

Deep Neural Network

Deep Neural Network